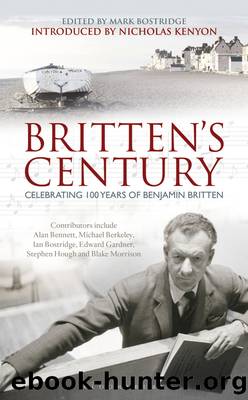

Britten's Century by Nicholas Kenyon

Author:Nicholas Kenyon

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Celebrating 100 Years of Benjamin Britten

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Published: 2013-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

Notes

iBritten had written out the full score at great speed and felt that it was too untidy for future use by other conductors; it was very unusual for a pre-publication full score not to be in his own hand.

iiBritten never composed at the piano, but he would play through what he had composed each day âto fix the music in timeâ, as he once explained to me. He went on to say that he had once, during the composition of Billy Budd, written an extended passage without recourse to the piano, and that the timing had consequently gone wrong.

iiiDonald Mitchell describes being sole audience to a complete performance of the opera, with Britten taking all the parts, in December 1972, in his introduction to the Cambridge Opera Handbook Death in Venice. A subsequent âperformanceâ was given to a small audience of those who would be involved in the production, including Colin Graham and John and Myfanwy Piper.

ivRosamund Strodeâs account of the genesis of the opera in the Cambridge Handbook, A chronicle, is indispensable, containing greater detail about specific musical issues than I have given here.

vThe 350 pages of my handwritten vocal score are now in the Britten-Pears Foundationâs archive.

viThere is no division into acts in the composition sketch, and Rosamund Strode says that the final decision was not taken until December 1973. However, in a letter to Myfanwy Piper written in February 1972, Britten speaks clearly of âAct Iâ and âAct IIâ

viiIn Humphrey Carpenter, Benjamin Britten, p. 546

viiiOther interpretations would doubtless have been made had Myfanwy Piperâs suggestion that the boys dance naked been pursued. Donald Mitchellâs description of this proposal as âsomewhat unworldlyâ (Cambridge Handbook p. 13) is a masterpiece of understatement. It is significant, though, that this is one of the few Britten operas where no childrenâs voices are heard.

ixMyfanwy Piper writes of the difficulty of reconciling âthe comparative austerity of language required by the composer with the extreme wordiness of the textâ in her account of the libretto in the Cambridge Handbook.

xSee my article âThe Venice Sketchbookâ in the Cambridge Handbook.

xiâUsually I have the music complete in my head before putting pencil to paper. That doesnât mean that every note has been composed, perhaps not one has, but I have worked out questions of form, texture, character and so forth, in a very precise way so that I know exactly what effects I want and how I am going to achieve them.â In Murray Schafer, British Composers in Interview (1963: the interview was given in 1961).

xiiRosamund Strode says that in May 1973 she listed 346 corrections to the vocal score and 415 to Act I of the full score (Cambridge Handbook, p. 41).

xiiiAn invoice in the Britten-Pears Foundation archive shows that I worked 22½ hours in Aldeburgh during March (for which I was paid £2 an hour).

xivCambridge Handbook, p. 71

xvCambridge Handbook, p. 41

xviThe German translation was made by Claus Henneberg and Hans Keller, but it was a collaboration in name only. I have a copy of the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32268)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31890)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20460)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18989)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18592)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17704)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17391)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16986)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16948)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16665)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14610)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14460)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14035)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13636)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(13014)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11791)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(9038)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8940)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8869)